December 14th, 2011 — baltimore, business, design, economics

It can be difficult to see the forest for the trees when it comes to defining what it is we in the so-called “tech community” are trying to achieve.

The confusion begins with names: some call it the “startup community,” the “tech business community,” or #BmoreTech. Whatever. I’ve been splitting these hairs for several years now, and with the help of many others and after many personal experiences with organizing groups, events, venues, and businesses have developed a simple but powerful vision for the community.

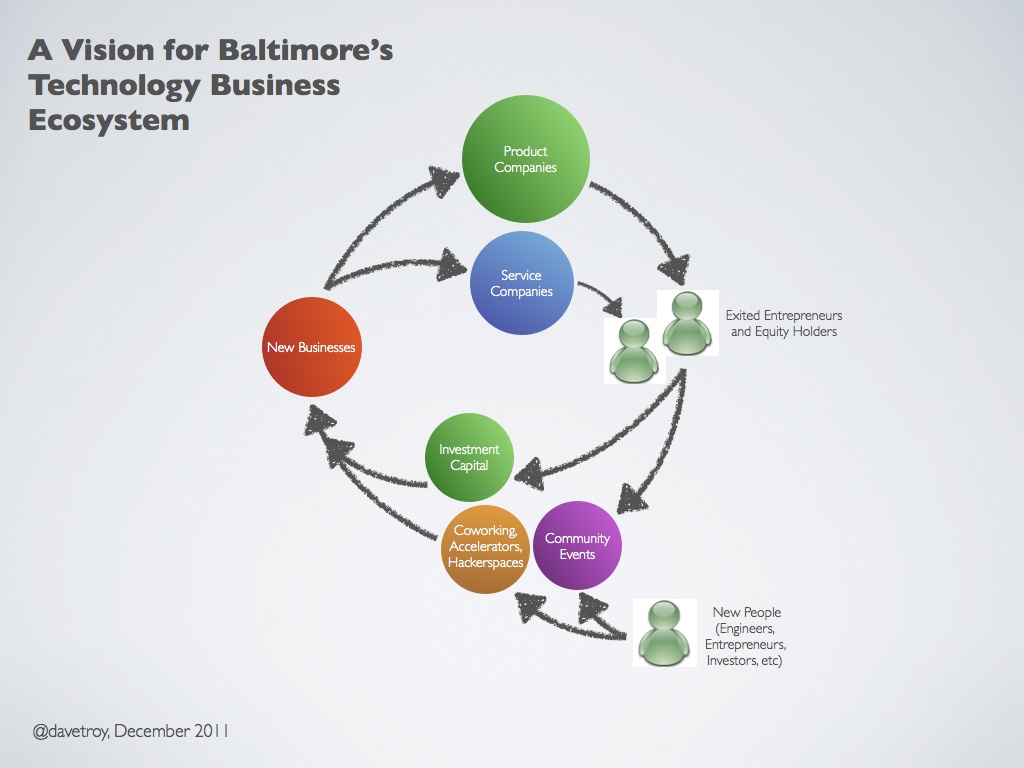

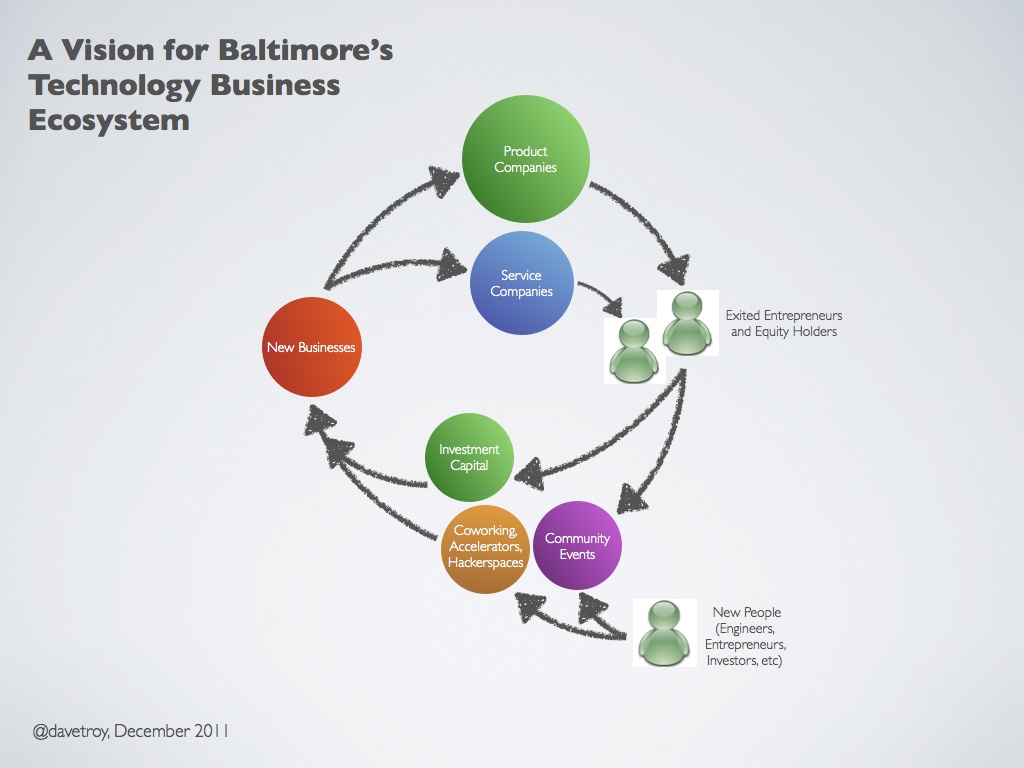

We’re all trying to build an ecosystem that looks something like this (click to enlarge):

Before we get into the specifics of this vision, here are a few basic values that underly it:

- People are the lifeblood of the community. The ecosystem requires educated, creative people. We should strive to enrich and build compelling opportunities for the people in our community.

- Businesses generate the wealth that powers our community. Strong businesses make a strong community. We should aim to make our businesses stronger and more valuable.

- There is a role for everyone. Diversity of expertise and background is essential to a strong business community. We should aspire to have a healthy mix of product companies, service companies, business service providers, and many types of venues and events for relationship building.

- We should celebrate our successes. Celebrating successes, whether they are successful exits or just milestones, is essential to creating a community that values growth, curiosity, and experimentation.

- We should connect people together. Trust and strong relationships are a precursor to new business formation. With strong trust relationships, we’ll have more new businesses and they will be more successful.

With this in mind, here’s how this model works, step by step. It’s a cycle, and for simplicity, we’ll start at the bottom.

- Getting into the mix. (6 o’clock) New participants, exited entrepreneurs, investors, hackers, new entrepreneurs come together via a mix of venues and events. By “venues” I am talking about spaces that offer opportunities for daily, ongoing interaction between individuals. They’re “high touch” while being “low risk.” Think coworking, hackerspaces, regular café coworking, incubators and accelerators, and educational institutions. By “events” I’m talking about one-off or periodic events that afford people an opportunity to get together, get to know one another, and try new things. (Think Bmore On Rails, Startup Weekend, EduHackDay, CreateBaltimore, etc.) New investors can participate in angel groups and pitch events.

- New business formation, access to capital. (9 o’clock) With trust, exposure, and experience, new businesses can form. With the prolonged exposure made possible by the “mix” phase, entrepreneurs can make more informed decisions about who to go into business with and have likely had more time to refine their ideas before ever beginning. This means a lower failure rate for new startups than in a less-developed ecosystem. As for investment capital, some will come from exited entrepreneurs, some from venture capitalists, seed funds, and governmental initiatives like TEDCO and InvestMaryland. We should aim to connect investors with nascent businesses. This will happen naturally to some extent in the “mix” phase, but we should consciously encourage it; bootstrapping should also be an option.

- Business growth. (12 o’clock) Some companies will grow to become strong product companies, others will become service companies. Some people want to grow their businesses to sell them, while others just want to build and run a great business. These approaches are all valid. We should celebrate the formation and growth of all of the companies in our ecosystem.

- Entrepreneur exits. (3 o’clock) Some entrepreneurs will seek the opportunity to exit their businesses and capitalize on their growth. This is most lucrative with product companies. When these exits occur, we should celebrate them as successes of the community as a whole.

- Entrepreneur returns to the mix. (6 o’clock) Exited entrepreneurs should be encouraged to re-engage with the community, either as investors or as active entrepreneurs to form new relationships and new businesses. The cycle starts anew.

That’s really it. If we can make this cycle work, we’ll have a thriving entrepreneurial ecosystem in Baltimore. (This is the exact same cycle that made Silicon Valley great, and is now working in places like Boston, Austin, and New York.)

That’s Great, But Where Do We Stand Now?

We have much of what we need in place: venues, events, investors, and businesses. But the two things we have most lacked are a cohesive vision for how this cycle is supposed to work, and also the last link in the cycle – systematically re-engaging entrepreneurs into the ecosystem.

However, just today came the news that Greg Cangialosi and Sean Lane are forming a startup accelerator in Federal Hill. That’s an example of two successful entrepreneurs getting back into the mix and re-engaging. We need more of that. But we need to make it easier and more attractive for entrepreneurs – there need to be obvious on-ramps and channels. We’re starting to get that in place.

My hope is that this vision, which I have shared in one-on-one conversations with many friends and leaders to much enthusiastic agreement, can now take root as the underlying force that animates our community.

Role of the Greater Baltimore Technology Council

There’s been much discussion about what the role of the Greater Baltimore Technology Council should be, and I submit that this vision, as I’ve articulated it here, is what the group has been moving toward for the last three years – and with Jason Hardebeck (who is himself an exited entrepreneur) at the helm, I believe we can move towards it more quickly now.

The GBTC’s job is to:

- Help build and protect the ecosystem. GBTC should be a watchdog that ensures the ecosystem has the right pieces in place and that they have what they need to function properly. This means working with government, educational institutions, and others to ensure that the conditions required for the ecosystem to thrive are present.

- Accelerate the cycle. The faster this ecosystem operates, the more successful we will be. Specifically, GBTC should connect people together, and celebrate our collective achievements, and help pull our educational institutions into the ecosystem. Ultimately this will pull in more smart, creative people, accelerating the cycle further.

- Make our businesses stronger. By connecting our community together better and providing venues, events, connections, and celebrating our success stories, GBTC can help to make each of our businesses stronger and more robust. This also means connecting businesses to service providers (HR, insurance, accounting, legal) and mentors who can provide value.

For all the drama and hand-wringing, it really is this simple!

Some have wondered whether they “belong” in the GBTC. That’s something every person and entrepreneur has to decide for themselves; there are obviously many valid and valuable ways to participate in this overall vision that are outside of the scope of the GBTC. However, if you care about growing and protecting this ecosystem, and if the group can help your business grow and succeed, I’d encourage you to lend GBTC your support; it just makes good business sense, as GBTC is the only group that has been tasked with this important work.

I know that others in positions of leadership in Baltimore’s tech business community (and at GBTC) share this vision. I encourage your comments and feedback, but before reacting, you might take some time to really think this over. This is something I’ve been looking at for several years, and based on everything I know, this is the right way forward.

The Rest of the Story

Oh, and there’s one more thing.

We all want to prime this pump and get this vision more fully underway, but I also think it’s reasonable to ask how Baltimore’s tech ecosystem fits into the bigger scheme of things. What relationship should we have with other ecosystems, in our region and around the world? Is the point to win or are we trying to thrive? I’ll be touching on this topic in an upcoming post, and it should help to clarify how this vision makes even more sense for Baltimore.

November 15th, 2010 — baltimore, business, design, economics, geography, philosophy, politics, trends

Last week another Maryland elected official, Prince George’s County Executive Jack Johnson, was arrested – along with his wife – on federal corruption charges. And once again, land development deals were the problem: a relatively inexperienced public official was lured by small profits gained by handing out development deals to a few cronies.

Shockingly, the press and the public feign surprise every time this happens. The Washington Post’s coverage of the Johnson arrest earnestly reports that the county seems to have developed a “pay to play” culture – and that you “don’t hear that about other jurisdictions.”

What about Baltimore city, where just nine short months ago former Mayor Sheila Dixon was convicted for accepting gifts and bribes from developers? Granted, Dixon was dealing in a few thousand dollars worth of gift cards and baubles while Johnson and his wife were flushing $100,000 checks and stuffing tens of thousands of dollars in their underwear. But one gets the impression that this may be a result of Dixon’s relative inexperience. Given more time, she would likely have learned to ask for more.

How did we get here? How is it that public-private development deals can be handed out to cronies and first-time “developers?”

First, too many people that seek public office expect to be financially enriched by it. There’s a reason it’s called public “service” – it is meant to be a sacrifice made in exchange for the opportunity to participate in private enterprise. When politicians go into office expecting that the power of public office should also include big money, they’ll be disappointed. Only crooked deals can fulfill those expectations.

Second, we have collectively lost sight of what “development” actually means. Today when people say “development,” they almost always mean turning an unsuspecting piece of land “into” something, whether it’s houses, a shopping mall, a hotel, or a stadium. And sometimes that fulfills a real need.

But too often, these are projects that we don’t truly need – but they do hold the potential to make a few people pretty wealthy. A small-time developer can double his wealth over a few years. But like a small-time addict, the beast must be fed: with new land, new projects, new deals. Because very often the gains are one-time hits. A housing project might make a five time return on investment. To keep the perpetual motion machine going, there must always be new deals.

This is where local elected officials come in. Mayors and county executives have just enough power to direct their agenda towards development projects that can enrich developers. Often, cronies of elected officials will become developers just to take advantage of their proximity to this fresh supply of new land deals. This seems to have been the case with Johnson. One of Johnson’s golf buddies had never developed anything, but was given a no-bid contract on a major project. This constitutes an illegal squandering of public funds.

Maybe it’s time to rethink what we mean when we use the word “development.” Do we really need to develop more strip malls, hotels, and suburban housing? In a place like central Maryland, we’re darn near out of land anyway. So this pyramid-scheme of land development has to stop. The corruption will only stop when local elected officials stop thinking that no-bid or restricted-bid contracts for major development deals actually move anything forward.

Instead, let’s start thinking about “development” in terms of “resource allocation.” How are we going to allocate scarce public resources to enrich our citizens through education, equal opportunity, and in repairing and maintaining the infrastructure and buildings we already have?

If the goal of “development” is to advance the economic opportunity and prosperity of the people of our state, maybe we should start by valuing our landscape. Instead of cluttering it up with mile after mile of pointless suburbia, let’s invest in places that mean something to the people that live there. Let’s make the places we have better. Let’s fix blight and make transportation systems that work. Let’s plant trees and make bike lanes.

Development should be about developing our people and making what we already have work more efficiently, not in building shoddy new projects that devalue existing assets and clutter our landscape.

And when contractors are required, let’s put the bidding online, require each bidder to go through the same qualification process, and let the lowest, most qualified bidders win.

When the public changes its perception of what development means, we will have fewer politicians who see elected office as a get-rich-quick scheme. Every time another politician is caught in these shenanigans, the public trust in government is undermined.

So a change in public perception about the nature of development can actually lead to a tangible restoration of public trust in government, and that can’t come too soon.

July 31st, 2010 — baltimore, business, design, economics, geography, philosophy, politics, software, trends

I live in Baltimore, in the great state of Maryland. I’ve been studying the economic development process here for many years. While this post contains observations specific to Maryland and Baltimore, the concepts likely apply in other geographies as well. I am curious to hear your perspectives from where you live.

Shh… they don’t know they’re obsolete!

Shh… they don’t know they’re obsolete!

There’s a growing disconnect in economic development. Government sponsored economic development outfits are tasked with 1) growing the tax base, 2) attracting new businesses, 3) helping existing businesses grow, 4) aid in the creation of new businesses, 5) develop and grow the local workforce.

In Maryland, the State Department of Business and Economic Development traces its roots back to the Bureau of Statistics and Information, which was formed in 1884 to compile statistics about agriculture and industry. As industry shifted dramatically in the 1950’s and 1960’s, the focus shifted to providing small business loans and seeding the development of new jobs.

Vast consolidation in manufacturing starting in the 1970’s meant that states were particularly anxious about job losses. The loss of a single plant could deal a staggering blow to the tax base, and could mean a huge loss of jobs — often leading to a demoralized workforce and a downward spiral of negative economic growth. (Think Detroit.)

The Zero-Sum Game

As a result of this process, states began to engage in heated battles to attract and retain manufacturing facilities. The primary tool available to economic development authorities has traditionally been tax credits and other “incentives,” which might include deferred taxes, regulatory considerations, and a “turnkey” permitting process.

As states rushed to use these tools to attract and develop these “big projects,” a kind of zero-sum game emerged between states trying to attract companies and capital. Large corporations were now in a position to effectively “shop” for the sweetest incentives. As you likely know, states have not shown much restraint in their willingness to offer breaks. In fact, it’s all been very embarrassing — a rush to the bottom, where states compete not on their own merits, but on how many baubles they can afford to dole out to their latest suitors.

This disease has so stricken governments, Governors, and their economic development teams that they’ve developed an unhealthy obsession with “big projects” as well. Folks in government, who on average have very little first-hand experience with entrepreneurship or business, tend to think in “causal” terms. If we do X, then Y will happen. And so the logic is that if you want a big result, take a big action.

And so they chase after smokestacks and big iron, trying to attract heavy manufacturing, big developments by big developers, corporate headquarters, sports teams, stadiums, and slot parlors. But here’s the paradox: these projects, while flashy, just don’t pay off. Tax subsidies are never recouped, and the jobs that are created tend to be bottom-of-the-barrel service industry jobs that barely support a living wage.

Baltimore’s subsidized Camden Yards stadium produces $3 Million per year in tax revenue, but costs Maryland taxpayers $14 Million per year in subsidies. The heavily subsidized Ravens stadium produces $1.4 Million per year but costs taxpayers $18 Million. Failure to impose or enforce job quality standards as part of subsidy packages provided to multiple hotel developments in Baltimore has led to many low-wage jobs and nearly none of the higher paying jobs that were promised. (These conclusions were taken from this report by the group Good Jobs First.)

New Approaches

Maryland, in an effort to develop a strategic focus on biotechnology, instituted a $6M program of tax credits (later increased to $8M) for investors in biotechnology companies. The program has proved wildly popular, and to Maryland’s credit, it recognized the importance of investing in an industry that had already taken root here and, thanks to the presence of the National Institutes of Health and Food and Drug Administration, was a natural strategic focus for our area.

The only question is how effective the biotech tax credit is at actually developing these kinds of jobs in the long term. It’s a little early to judge how effective the biotech tax credit program will be, but we can make these qualitative observations about that industry:

- Developing a new biotech product (whether a drug, device, or process) has a very long lead time.

- Because of long lead times and the need for highly-skilled workers, development is very expensive.

- Failure is common and is often stark: big bets on molecules that don’t pass approval processes or are copied by competitors can lead to epic financial losses.

- The kicker: successful companies are often acquired by firms based elsewhere, leading to job losses or relocations, ultimately undoing the benefit originally intended.

I do not want to overemphasize the potential downsides; there are many tangible benefits of this program both now and in the long term. The only question is whether we can do better.

Betting On Ourselves

What if, instead of trying to offer subsidies to outsiders, we start investing in ourselves? A tax credit for biotech is a step in that direction, but what could we do with a comparable program for Internet and IT startups? What if we made investment capital available to Maryland businesses as part of a strategy to develop new companies that actually stay here for the long term (and are not susceptible to subsidy bribes from other locales)?

A new program called Invest Maryland has been proposed by Governor Martin O’Malley, and is based on similar programs instituted in other states. The program would make $100 Million in venture capital available to Maryland businesses. Funds would come from tax prepayments made by insurance companies in exchange for tax credits. The theory is that the cost of the tax credits would be exceeded by the benefit in business development provided by the venture investments.

Done properly, this is probably a very sound program. But to be maximally successful, I believe we need to start placing strong bets on information technology startups in particular:

- IT startups are very capital efficient. Thanks to lean startup methodologies, IT startups can get up and running for as little as $50,000 to $150,000 in investment.

- Maryland already has the highest concentration of information technology workers in the world. It’s a strong strategic fit for exactly the same reasons that biotech investment is a good fit.

- To achieve strong returns with early stage investments, it’s often necessary to invest in 150 or more companies. The small capital requirements of IT companies allow for many more investments to be made with less capital, thus increasing the odds of success.

- A large portfolio of seed-stage IT investments can yield internal rates of return of up to 25-30% annually, which is terrifically high. That is in addition to the benefit of building a permanent base of IT businesses in Maryland, and all the job and tax-base benefits that would bring.

- A large number of ventures would, statistically, also have to produce a large number of failures. This culture of continuous endeavor would de-stigmatize failure and allow for repeated teaming and relationship building. Inenvitable losses are not losses, but in fact fertilize the forest floor — building the ecosystem for the long term.

- A culture rich in startups will keep us from exporting our best and brightest to other places, which we do routinely right now.

$10M for IT Startups

As Maryland’s leaders and legislators consider the Invest Maryland initiative, I propose that the state set aside $10M of its $100M fund specifically for IT startups. With that $10M, I propose that Maryland invest in up to 200 seed stage IT firms at anywhere from $50K to $150K per company.

Doing this well will be difficult. However, by partnering with existing entities such as Baltimore Angels and members of the business community, we can make that investment maximally productive. We’d need to figure out the details, but we can’t expect government employees to make these investments on their own without domain expertise. By leveraging the people in the community that want to see these investments occur and who do have appropriate domain expertise, we can dramatically increase the effectiveness of this fund.

And if the initial $10M investment proves effective, we should consider enlarging the program to $25M or higher later. This strategy carries very little risk for the state and would create a stunning worldwide buzz about the vibrancy of the startup culture in Maryland, and would highlight the innovative private-public partnership that sparked it.

Thinking Small

The businesses we routinely cite as our biggest successes — Under Armour, Advertising.com, SafeNet, Sourcefire, Bill Me Later, to name a few — all came about as home-grown successes. They are not here because we brought them here from someplace else. They’re here because they were grown here from scratch, by people who love it here.

If we start now, placing a large number of bets on our brilliant citizenry, we will do something remarkable: we’ll launch a virtuous cycle of entrepreneurship — the opposite of the kind of downward spiral associated with the rust belt era.

Instead of the simplistic “causal logic” associated with “big” economic development, we’ll be using the logic of entrepreneurial “effectuation,” of the kind promoted by entrepreneurship researcher Dr. Saras Sarasvathy.

It is the combined effects of many people pursuing entrepreneurship that will lead us someplace extraordinary. Suddenly, Baltimore (and Maryland) will become the cover story on the airline magazine — the “hot” place to be. One (or ten) corporate headquarters relocations will never do that, because it won’t bring about endemic entrepreneurship in the culture.

Making lots of small bets instead of fewer “big” bets makes government nervous. Everyone wants to be seen as someone who accomplishes something big, and with short gubernatorial terms, it’s tough to get ramped up with plans that might take 10 or 12 years to realize. But that’s exactly what’s needed.

We need to resist the temptation to focus solely on big development, and instead bet on the tiny startups. The big wins will come when these firms flower, and the ecosystem that gave them life comes into its own. Yes, that might happen on someone else’s watch — but it’s still the right thing to do.

A recent report from the Kauffman Foundation proclaims, “Job Growth in U.S. Driven Entirely by Startups.” If this is the case, Lord knows we could use a lot more startups. If we want new jobs — and not jobs poached from other states at great expense and flight risk — the only logical choice is to focus on creating new startups.

And if solid returns of 25-30% can be realized on a large portfolio of startups, shouldn’t we drop almost everything else and focus only on that?

The first state that adopts this strategy will be sowing the seeds of an incredible, dynamic culture of entrepreneurship. Is Maryland ready to take the challenge?

May 13th, 2010 — business, design, economics

I’ve been meditating on these two ideas, and they resonate for me. See what you think of them.

The Building

Imagine taking the roof off of your building and shaking out all of the people inside.

Now, rearrange the people into an optimal value-producing configuration.

I would bet that you could find a handful of combinations that unlock $1 billion in value; I’d bet you could find a few that unlock $10+ million in value; and I’d bet that 50% of the available combinations would unlock more value than the existing configuration.

What are the barriers that keep us from unlocking maximum value in our workforce? Walls, lack of connections, non-optimal application of resources, and addiction to personal cash-flow spring to mind.

Why do we perpetuate these non-optimal configurations of resources? What are you doing to unlock the potential in your building and in your broader community?

Keep the Same Team?

The more exposure I have to the world of startup investing (and to startups themselves) the more convinced I am that team is everything. At first I was more apt to evaluate a startup by its idea and its market metrics. But I’ve come to believe that all bets are bets on people.

In support of this strategy, I’ve started to look for heuristics that indicate that a particular team is worth betting on. And one question I am asking founders is this: If you do secure funding, would you keep the same people or would you hire new team members?

The answer can be revealing. If they indicate that they will keep the same team members, it’s worth asking why. And understanding the why behind the why. If there are good reasons why the team is well-cast, then this is likely a bankable team. Good reasons include expertise and real dedication. Bad reasons may include “knew them at my last job,” “he built it under contract,” or “found him at a meetup.”

There’s no hard and fast rule here, but the key thing to remember is that money changes everything. But if it changes too much of your team make-up, it’s probably not a bankable configuration to begin with.

How are you rearranging the world around you to produce optimal, bankable teams? To me, this is the essence of entrepreneurship. What do you think?