Combinatorial Innovation

There are so many new technologies today: tablets, geolocation, video chat, great app frameworks. It is easy to cherry-pick off “combinatorial” innovations that seem compelling, and can maybe even be monetized readily.

But all those innovations are inevitable. If our technologies afford a certain possibility, they will occur. “That’s not a company, that’s a feature,” is one criticism I’ve heard of many “startups.”

These combinatorial, feature-oriented “X for Y” endeavors are often attractive because they can often be built quickly.

Startup Weekend events send an implicit message that a meaningful business can be fleshed out in just a couple of days. And I argue that is not true. That might be a good forum to get practice with building a quick combinatorial technology and working with others, but a real innovation, much less a meaningful business, takes real time.

I think people are often looking in the wrong places for innovation, often because they don’t really take the time to do the homework, observation, and deep reflection necessary to arrive at a true insight. We want things to be quick and easy.

Changing Minds, and Behaviors

The biggest innovations require asking people to change their beliefs, habits, and behaviors.

iPhone: “why would I want a smartphone without a physical keyboard? It’s too expensive. I can’t install apps.”

Twitter: “what is this for? Why would anyone do this? Who cares what I had for breakfast?”

iPad: “an expensive toy. Could never replace a real laptop. Can’t run real office applications. The enterprise will never adopt it.”

Foursquare: “only hipsters and bar hoppers would ever do this. They are letting people know when to rob them. I don’t want people to know where I am.”

And these innovations have taken years of constant attention to bring to their current state. And they are not done.

One Innovator’s Story

Dennis Crowley, founder of Foursquare, was in the room at Wherecamp in 2007 where I was giving a talk about location check-in habits via Twitter (a subject I knew well because of my Twittervision service, which allowed this.)

Dennis, of course, also founded the precursor to Foursquare, Dodgeball, which he sold to Google in 2004 (they promptly killed it.)

But Dennis wanted to see his vision come to pass, and he knew it would someday be possible — though at that point the iPhone had not been released and it would be nearly two years before it supported GPS location technology.

But there Dennis was, doing his homework in 2007, studying user behavior to figure out exactly what behaviors he would have to encourage to make Foursquare work.

He asked me, “so, people are really putting their home and work locations formatted inside tweets in order to update their location?”

“Yep, a few thousand times a day,” I replied.

“That’s cool. That’s really cool stuff,” he said. And from that, and years of similar evidence-gathering and study, Foursquare would be born.

So, creating Foursquare took about five years. (I could have “stolen” the idea and built Foursquare myself. But I didn’t execute on that; it was his vision to pursue.) Dennis did his homework. He was prepared. And his vision preceded the technology that enabled it.

Why, not How

Real innovation doesn’t come from a weekend. It comes from passion, years of study, understanding deep insights and the “why,” and persistence in seeing something new to market, along with the marketing and cheerleading that will make it successful.

The iPad owes much to Steve Jobs’ love of calligraphy. He cultivated a sense of aesthetics because of that initial interest. He didn’t set out to “make money” but rather dedicated himself to changing the world for the better using the entirety of his humanity. Time studying art wasn’t “lost,” it was R&D for the Mac, iPhone, and iPad.

Many of today’s entrepreneurs could stand to do less “hustling” and more reading, exploring, reflecting, and gathering input — and when it is time to make stuff, set their sights as high as possible.

There is more to this world than money, and there are countless opportunities to make it a vastly better place. Rather than using our CPU cycles just playing with combinatorial innovations, let’s devote ourselves to making the world as amazing as possible. Try to take time to reflect on how you can make the world better, and not just on what current technology affords.

Google CEO Eric Schmidt recently outlined a case arguing that America needs to address its ongoing “innovation deficit” and spur entrepreneurship and creativity in meaningful new ways.

How did we get here? Why is it that America has an innovation deficit? It’s simple: we have lulled ourselves into complacency. America is bored because we have made ourselves boring.

Unleashing Self-Actualization

What do we mean when we talk about innovation and creativity? Really what we’re talking about is what psychologists call self-actualization. Put simply, it’s nothing more than realizing all of your unique capacities and putting them to good use. Self-actualization occurs best when it’s in the company of others who are doing the same. Companies that achieve remarkable results are typically loaded with people who are either self-actualizing or on a pathway towards it.

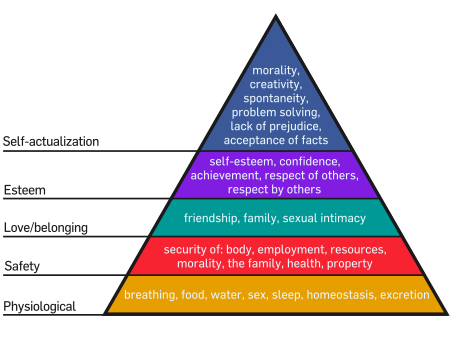

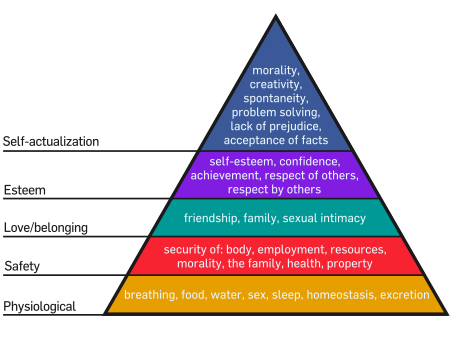

Abraham Maslow described this pathway as the “hierarchy of needs” to highlight the fact that people cannot become fully self-actualized if they are concerned with other more basic needs like food and security.

Like the USDA food pyramid, Maslow’s hierarchy identifies some important elements, but the idea that there is a strictly linear progression towards self-actualization, or that it is inclined to occur naturally, is probably wrong. Looking at the world around us, it’s easy to see examples of people whose lives who have petered out somewhere in the middle of his pyramid, even though their baser needs have been met.

I believe this is because we have designed 21st century America in such a way that we short-circuit the process of self-actualization in a number of important ways.

Problem 1: Suburbs

Self-actualization occurs best when people are able to connect face-to-face to discuss real-world ideas, try things out, and play. This means intellectual conversation with a diverse range of people, including a broad range of views. It means exposure to the arts, to music, and a shared desire to solve meaningful problems.

Suburbs short-circuit these important pathways for self-actualization in these important ways:

- Slowing movement: people are dispersed – gathering requires use of cars

- Lack of diversity: suburbs tend towards less diversity of views, not more

- Diverts self-actualizing motivation into materialistic and trivial pursuits

The first two points are obvious enough, but let’s spend a moment on the last one.

Suburbs divert self-actualization into pursuits like neighborhood-hopping and home improvement. It’s not surprising that we just suffered the effects of a housing bubble. With millions of peoples’ self-actualizing efforts poured into drywall and granite countertops, there was simply a limit to how much housing and home-flipping we can endure. It doesn’t do anything. Working on housing is first-order toiling, not long-term advancement.

Is it surprising that the icons of the housing bubble years were “Home Improvement,” “Home Depot,” and the SUV? The SUV was literally a vehicle for improperly diverted self-actualization: if I have a vehicle that lets me improve my basement and my backyard, I can become the person I want to be.

Problem 2: Artificial Scarcity of Opportunity

Suburbs have had other unfortunate side-effects: we have allowed corporations to define the concept of work. By dispersing into our insulated suburban bubbles, we have largely shut down the innovative engines of entrepreneurship that used to define America. Where we might fifty years ago have been a nation of small businesses and independent enterprises, we are more and more becoming reliant on corporations to tell us what a “job” is and what it is not.

To the extent that we are not spending time together coming up with new important ideas, we are shutting down opportunities for ourselves. And corporations are happy to reinforce and capitalize on this trend. Opportunity is unlimited for people who are legitimately on a pathway towards self-actualization. We choose not to see it because we think of “jobs” as something that can only be provided by “companies,” and not created from scratch by collaboration.

Problem 3: Reality Television

Reality television is an ersatz reality to replace our own. It steps in where we’ve failed at self-actualization. It is both a symptom and a cause of our failure. As a symptom, it shows that we have so much time on our hands that we can spend it worrying about somebody else’s ridiculous “reality.” As a cause, this obsession can only be serviced at the expense of our own shared reality.

Problem 4: Car Culture

As a society, we spend way too much time in cars. Some of this is due to the issues I already raised about suburban design. But besides that, we spend a ridiculous amount of time stuck in traffic, waiting at red lights, and trekking around our metropolises.

Cars are fundamentally isolating. Time spent in a car is time you can’t spend doing something else. Sure, they can be useful, and I’m not anti-car, I’m just anti-stupid. If we as a society are burning many millions of hours each week in our cars stuck in traffic and covering unnecessary miles, it’s hard to see how that’s helping us become self-actualized (unless it’s in the backseat) and become more innovative. It’s a tax on our time.

Some have also suggested that one reason we have so many prohibitions on what we can do while driving is because we really just don’t like driving that much. Maybe the problem with “texting while driving” is that we are driving, not that we are texting. Maybe communication is more important societally than piloting an autonomous 3,000 pound chunk of metal and plastic?

A Solution: Well-Designed Cities

We’ve had the solution under our noses all along, but we’ve chosen to let our cities languish. Historical facts about America have led our cities to evolve in particular ways that differentiate them from some of our peers in Europe in Asia. But there is hope, and we must recognize the assets at hand in our cities.

Cities offer higher density populations which lead in turn to innovation and a flourishing of the arts. They lead to efficiency of movement and face-to-face communication, which is absolutely essential for intellectual self-actualization and entrepreneurship. Well designed public places let people interact and share, and also provide a platform for festivals, celebrations, and entrepreneurship. There are simply too many positive assets to ignore.

Arguments that American cities are unlivable today are tautological and self-reinforcing. The very problems that are most often cited (crime and education) are the same problems that would most benefit from entrepreneurship and real long-term economic development activity.

The root cause for the abandonment of our cities is race. In the case of Baltimore, WASPs left when Jews became concentrated in particular areas. Jews left when blacks became concentrated in particular areas. And “blockbusters” capitalized on the fear by benefiting on both ends of these transactions. In 50 years, Baltimore (and many American cities) changed dramatically.

Young adults today simply do not remember the waves of fear that sparked this initial migration. It may be a stretch to say that we are entering into a “color blind age,” but we do live in an era where we elected the first black president. I believe we are at the very least entering an age where people are willing to consider the American city with fresh eyes.

We are at a turning point, on the cusp of a moment when people will start looking at our cities entrepreneurially, for the assets they possess rather than the history that has defeated them. We are at a point where we can forget the divisive memories of the mid-twentieth century and forge a future in our cities that is based on shared values of self-reliance, innovation, and entrepreneurship.

Designing Our Future

The design constraints we have proposed for the last 50 years — abandoning our cities, relying on cars, building suburbs and big box stores — have led to the America we see today. And I ask simply, “Do you like what you see?”

We’ve let the culture wars frame these difficult design problems for too long, and it’s time now to put them behind us and start to ask questions in fresh terms. It’s clear now the answer likely doesn’t involve old-school silver-bullets like “Public Transportation,” because simply overlaying transport onto a broken suburban design doesn’t fix anything. Building workable cities and investing in long term transportation initiatives that help reinforce a strong urban design is much more sensible.

And make no mistake: self-actualization is an intellectual pursuit, and the kinds of cities that promote real self-actualization, innovation, and entrepreneurship must become hotbeds of intellectual dialog. Truth and acceptance of facts is an underlying requirement for self-actualization, and we can no longer delude ourselves into thinking that a society built on suburban corporate car-culture makes economic sense.

To continue to do so is to prolong and widen America’s innovation deficit.