The American educational system deadens the soul and fuels suburban sprawl. It is designed as a linear progression, which means most people’s experience runs something like this:

- Proceed through grades K-12; which is mostly boring and a waste of time.

- Attend four years of college; optionally attend graduate/law/med school.

- Get a job; live in the city; party.

- Marry someone you met in college or at your job.

- Have a kid; promptly freak out about safety and schools.

- Move to a soulless place in the suburbs; send your kids to a shitty public school.

- Live a life of quiet desperation, commuting at least 45 minutes/day to a job you hate, in expectation of advancement.

- Retire; dispose of any remaining savings.

- Die — expensively.

Hate to put it so starkly, but this is what we’ve got going on, and it’s time we address it head-on.

This pattern, which if you are honest with yourself, you will recognize as entirely accurate, is a byproduct of the design of our educational system.

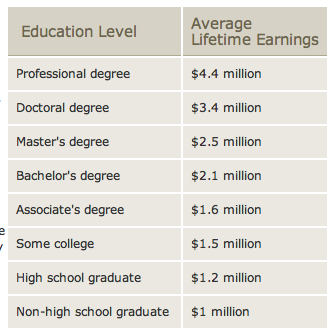

The unrelenting message is, “If you don’t go to college, you won’t be successful.” Sometimes this is offered as the empirical argument, “College graduates earn more.” Check out this bogus piece of propaganda:

But what if those earnings are not caused by being a college graduate, but are merely a symptom of being the sort of person (socioeconomically speaking) who went to college? People who come from successful socioeconomic backgrounds are simply more likely to earn more in life than those who do not.

There’s no doubt that everyone is different; not everyone is suited for the same kind of work — thankfully. But western society has perverted that simple beautiful fact — and the questions it prompts about college education — into “Not everyone is cut out for college,” as though college was the pinnacle of achievement, and everybody else has to work on Diesel engines or be a blacksmith. Because mechanics and artists are valuable too.

That line of thinking is the most cynical, evil load of horse-shit to ever fall out of our educational system. Real-life learning is not linear. It can be cyclical and progressive and it takes side-trips, U-turns, mistakes, and apprenticeships to experience everything our humanity offers us.

The notion that a college education is a safety net that people must have in order to avoid a life of destitution, that “it makes it more likely that you will always have a job” is also utterly cynical, and uses fear to scare people into not relying on themselves. Young people should be confident and self-reliant, not told that they will fail.

And for far too many students, college is actually spent doing work that should have been done in high school — remedial math and writing. So, the dire warnings about the need for college actually become self-fulfilling: Johnny and Daniqua truly can’t get a job if they can’t read and write and do math. See? You need college.

An Education Thought Experiment

I do not pretend to have “solutions” for all that ails our educational system. But as a design thinker, I do believe that if our current educational system produces the pattern of living I noted above, then a different educational system could produce very different patterns of living — ones which are more likely to lead to individual happiness and self-actualization.

If we had an educational system based on apprenticeship, then more people could learn skills and ideas from actual practitioners in the real world. If we gave educational credit to people who start businesses or non-profit organizations, and connected them to mentors who could help them make those businesses successful, then we would spread real-world knowledge about how to affect the world through entrepreneurship.

If more people were comfortable with entrepreneurship, then they would be more apt to find market opportunities, which can effect social change and generate wealth. If education was more about empowering people with ideas and best practices, instead of giving them the paper credentials needed to appear qualified for a particular job, it would celebrate sharing ideas, rather than minimizing the effort required to get the degree. (My least favorite question: “Will that be on the test?”)

Ideally, the whole idea of “the degree” should fade into the background. Self-actualized people are defined by their accomplishments. A degree should be nothing more than an indication that you have earned a certain number credits in a particular area of study.

If the educational system were to be re-made along these lines, the whole focus on “job” as the endgame would shift.

“A sturdy lad from New Hampshire or Vermont, who in turn tries all the professions, who teams it, farms it, peddles, keeps a school, preaches, edits a newspaper, goes to Congress, buys a township, and so forth, in successive years, and always, like a cat, falls on his feet, is worth a hundred of these city dolls. He walks abreast with his days, and feels no shame in not ‘studying a profession,’ for he does not postpone his life, but lives already. He has not one chance, but a hundred chances.” — Ralph Waldo Emerson, Self Reliance, 1841

And so if the focus comes to be on living, as Emerson suggested it should be, and not simply on obtaining the job (on the back of the dubious credential of the degree), then the single family home in the suburb becomes unworkable, for the mortgage and the routine of the car commute go hand-in-hand with the job. They are isolating and brittle, and do not offer the self-actualized entrepreneur the opportunity to meet people, try new ideas, and affect the world around them.

The job holder becomes accustomed to the idea that the world is static and cannot be changed through their own action; their stance is reactive. The city is broken, therefore I will live in the suburbs. The property taxes in the suburbs are lower, so I will choose the less expensive option.

Entrepreneurial people believe the world is plastic and can be changed — creating wealth in the process. But our current system does not produce entrepreneurial people.

Break Out of What’s “Normal”

It may be a while before we can develop new educational systems that produce new kinds of life patterns.

But you can break out now. You’ve had that power all along. I’m not suggesting you drop out.

But I will say this: in my own case, I grew up in the suburbs, went to an expensive suburban private high-school — which I hated — where I got good grades and was voted most likely to succeed.

I started a retail computer store and mail order company in eleventh grade. I went to Johns Hopkins at 17, while still operating my retail business. Again, I did well in classes, but had to struggle to succeed. And no one in the entire Hopkins universe could make sense of my entrepreneurial aspirations. It was an aberration.

I dropped out of college as a sophomore, focused on my business, pivoted to become an Internet service provider in 1995, and managed to attend enough night liberal arts classes at Hopkins to graduate with a liberal arts degree in 1996. This shut my parents up and checked off a box.

I also learned a lot. About science. About math. About philosophy, literature, and art. And I cherish that knowledge to this day.

But I ask: why did it have to be so painful and waste so much of my time? Why was there no way to incorporate that kind of learning into my development as an entrepreneur? Why was there no way to combine classical learning with an entrepreneurial worldview?

Because university culture is not entrepreneurial. And I’m sorry, universities can talk about entrepreneurship and changing the world all they like, but it is incoherent to have a tenured professor teaching someone about entrepreneurship. Sorry, just doesn’t add up for me. Dress it up in a rabbit suit and make it part of any kind of MBA program you like; it’s a farce. Entrepreneurship education is experiential.

I had kids in my mid-twenties and now have moved from the suburbs to the city because it’s bike-able and time efficient. And I want to show my kids, now ten and twelve, that change is possible in cities. I believe deeply in the competitive advantage our cities provide, and I intend, with your help, to make Baltimore a shining example of that advantage.

I don’t suggest that I did everything right or recommend you do the same things. But I did choose to break out of the pattern. And you can too.

Maybe if enough people do, we can build the new educational approaches that we most certainly need in the 21st century. This world requires that we unlock all available genius.