Entries Tagged 'business' ↓

February 14th, 2010 — baltimore, business, design, economics, geography, philosophy, travel, trends

Several months ago, this article from the Pew Research Center categorized several states as sticky, magnet, or both; sticky means that people who live there tend to stay there, while magnet means that it attracts people. Some states (Arizona, Florida, Maryland) are High Magnet/High Sticky, while others are one or the other, and one sad batch is neither (Iowa, New York, West Virginia).

What this study doesn’t tell us is very much about what those places are actually like, only the “raw numbers” about mobility and retention. For example, my home state of Maryland is described as “magnet/sticky” (woot) but so are Arizona and Florida, and as far as I can tell, these three states share little in common. Certainly the recent real estate bust was felt worse in those places than here.

I believe that in Maryland’s case, we are both the wrong kind of magnetic and and the wrong kind of sticky, and so to describe Maryland in this way is counterproductive because it assigns a positive spin to some inherently negative patterns of movement.

For example: suppose Maryland is “high magnet” because it attracts people who want to work for federal government contractors. This increases the per-capita income but puts pressure on roads, exacerbates suburban sprawl, and adds people to the voting base who often don’t understand local issues or have personal experience with the landscape around them. I’d call this effect neutral, if not negative.

Suppose Maryland is “high sticky” because we retain 99.5% of our college graduates (a number I’ve heard tossed around). But suppose we export .5% of our very best and brightest and our natural born “effectuators?” And suppose that the smart people we do retain get sucked into government? Again, not necessarily a bad thing, but it doesn’t necessarily lead to the most creative entrepreneurial landscape sometimes.

Maryland has a great deal going for it, but articles like this are meaningless and enhance a simplistic, 19th century view of how we want to build our society. Who are we building our society and economic structures for?

If we are building them for ourselves we need to start thinking about how they serve our everyday experience as people. I have more thoughts on this. If we want to build our society for corporations and a 19th-century conception of what education, production, and economic value is then idiotic oversimplifications like “high magnet, high sticky” might be useful.

I believe we can and must move past such Orwellian, disingenuous oversimplifications.

February 13th, 2010 — business, design, economics, philosophy, trends

Are entrepreneurs born risk-takers? Is there something about their personalities that predisposes them to take risks that others can’t stomach? Can entrepreneurship be taught?

According to entrepreneurship researcher Saras Sarasvathy, entrepreneurs aren’t different from anyone else; they simply adopt a different approach to problem solving.

Dr. Sarasvathy suggests that entrepreneurs actually create their own odds of success by taking incremental steps that move them closer to their goals. After being an entrepreneur for over 25 years and studying the behavior of many others, I think she’s right. She calls this incremental approach “effectuation” because it takes advantage of the compounding effects that the entrepreneur causes by their own actions.

Here are 6 key points to understand about Dr. Sarasvathy’s theory of effectuation:

- Entrepreneurs start with what they have and who they are. What do you know a lot about? What early or deeply personal experiences have affected you? What connections do you have? Leverage these assets to do something and then see what comes of it. This first step leads to additional opportunity, and sometimes these opportunities are very big and unpredictable. Action attracts others, and those others enhance opportunity and the odds of success.

- Entrepreneurs limit risk by understanding what they can afford to lose at each step. True entrepreneurs never take very much risk at once. Typically the calculation goes something like this, “I think it would be worth investing $50,000 in exploring this opportunity. If I lose it, I can survive. What’s the worst that can happen?” There are two likely outcomes of that reasoning: either the experiment is successful, in which case the investment is rewarded and leads to other follow-on opportunities, or the experiment is not successful, which most likely also will lead to other follow-on opportunities. Either way, new opportunities typically emerge because action attracts others.

- Entrepreneurs create their own market opportunity. When Burt Rutan set out to build Spaceship One, it was not because he perceived that there was a big market for expensive one-off spacecraft that was going unmet. He started with what he knew how to do and an affordable risk. When Pierre Omidyar started Ebay, he didn’t anticipate it would become a multibillion dollar company. Google’s founders Sergey Brin and Larry Page tried to sell Google for $1M, but were instead forced to see it through and become multibillionaires. The market for a company is often not clear at the moment of founding. Entrepreneurs find their way to the market by the creative, iterative leverage of what and who they know.

- Entrepreneurs trust people. The best entrepreneurs internalize the African proverb, “If you want to go fast, go alone; if you want to go far, go together.” To uncover large opportunities, it’s often necessary to coordinate the interests of many. The best entrepreneurs involve more people in the effectuation process, because more people means more assets, which often has a non-linear impact on the eventual outcome. In fact, Sarasvathy argues that a degree of calculated “over-trust” and “intelligent altruism” is a rational strategy for uncovering large multiplayer opportunities that would otherwise be hidden or impossible to achieve.

- Effectual thinking can be taught. Because entrepreneurship is just an application of effectual logic and not the result of innate personality traits, it can be taught. We do not accept the notion that “scientists are born, not made,” and even while we might believe that some people are more disposed to scientific work than others, we do not accept the notion that people cannot be taught to think scientifically. It is similarly possible to teach people effectual thinking. Tellingly, in communities where effectual thinking is common (Silicon Valley, for one), people who had not previously displayed effectual tendencies are often motivated to adopt the pattern once they see it can be effective at problem solving or in generating wealth. Effectual thinking may not only be teachable; it may be contagious in the right circumstances.

- Failure increases the odds of individual success. While the success rate of a typical individual venture might be quite low, an entrepreneur that sustains a failure is more likely to succeed in later rounds. Failure teaches the entrepreneur about affordable risk, suggests boundaries for over-trust behaviors, and offers hints about how to maximize opportunity. We should never stigmatize failure, but instead understand that it is part of the effectual process.

Pop Business Books

It is fashionable to tell people stories about Purple Cows, Tipping Points, Outliers, Whuffie, Crushing It, and practicing a Four Hour Workweek. However, these books all have their roots in effectual thinking. Do something. Utilize what you really know to stand out and be different. Work with others to uncover the opportunity you want to find. If books like this can motivate people to act, they’re probably a good thing. But I find they can be crazy-making because they don’t offer the intellectual underpinnings to explain why (or how) these approaches might actually work. They’re most often shaming you into action, and in the end they’re giving you a fish, instead of teaching you how.

Effectuation and Social Networks

The internet (in general) and social networks (like Twitter and Facebook, in particular) are platforms for effectuation. They allow entrepreneurs to find the people who will, at each successive stage, help to contribute to the success of their enterprise. These could be customers, partners, or investors. Any platform that allows like-minded individuals to find each other is an accelerant to the effectuation process. In fact, the like-mindedness of these stakeholders is more important than the roles that they play. What is the difference between a company and a customer when both are stakeholders in the product? Who is paying whom for what and when is a detail that needs tended to, but without finding the people who will participate in the conversation that maximizes the utility of the product, maximizing revenue will never be a consideration.

The Myth of the Visionary Entrepreneur

We give a lot of credit to successful entrepreneurs. Warren Buffett, Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, and Richard Branson are some of the most admired people in the world. In some ways that credit is deserved (though one could argue that civil servants and humanitarians are worthy of even more praise). However, we assign them too much credit, or at the very least we assign them credit for the wrong insights.

These people did not anticipate the circumstances of their success, and did not set out to attain the particular achievements for which they are most well known. Rather, these people are all master effectuators. They took action early. They involved others. They took many successive steps that moved them closer to their passions. They suffered failures. And perhaps most importantly, they are alive to tell about it.

There are many unsung heroes and master effectuators who have had great success but whose stories have ended less well. And we don’t hear as much about them. The final outcome should not diminish their achievement.

You do not need to be the next Bill Gates or Steve Jobs, or even have an idea right now, to be an effectual entrepreneur. Start now and take the journey. You will be glad you did.

References

January 9th, 2010 — baltimore, business, design, economics, geography, philosophy, politics, trends

This week saw the ending of a tragic saga that has been decades in the making. Baltimore Mayor Sheila Dixon negotiated a plea agreement to obtain Probation Before Judgment in which she promised to resign as mayor within 30 days. She entered an Alford plea, in which she did not admit guilt but admitted that the prosecution had sufficient evidence to convict her.

But the real story here isn’t about Dixon; it is about the long-term systemic abandonment of public life by the American citizenry.

And I use that term loosely. Americans take a cynical eye towards civics and citizenship. Public servants are routinely portrayed as buffoons and as half-witted wards of the state. Politicians are universally derided as corrupt, megalomaniacal, and intensely self-interested. Depending on the election, Americans vote in anemic numbers. Children are no longer seriously raised with the idea that civic engagement or public service is a kind of higher calling.

We are now consumers of politics rather than participants in civic life. And the accompanying “fanboyism” that we see in consumer behavior has effectively destroyed intelligent political discourse. Presumably somewhere out there there is a sticker of Calvin Elephant pissing on a Democrat Donkey. Enough.

The Dilemma of the American City

A confluence of factors over the last 90 years has drawn people from the urban core to the suburbs: air quality, the invention of the automobile, the Great Depression, unchecked suburban planning, school policy, racial prejudice and realignment, blockbusting profiteers, the end of urban manufacturing, ineffective urban planning, drug use, tax imbalances, poor transportation infrastructure, and incompetent city governments.

This has resulted in cities that have neither the tax base nor the level of civic engagement required to operate. The politicians do not have the skill or vision to initiate meaningful change. The population wants improvement and change but is often unwilling to exchange their short term interest for any long-term good. Surrounding jurisdictions point fingers at the city, and the problems become self-reinforcing. For each day that our cities slog on in dysfunction, the more people are convinced that dysfunction is a permanent and intractable condition.

To change things in the long term, we need to attract people back into our cities. And there are workable strategic reasons why this is possible: cities provide real competitive advantage, particularly for industries based on ideas and information.

Urban Feudalism

It is not a coincidence that the graft case against Dixon was centered around her relationship with multiple developers. This 2008 City Paper article gives a good sense of the shadowy web of relationships surrounding the Mayor, her predecessor, and developers.

It requires a special kind of optimism to think that the gift cards, cash, and other baubles that Dixon received were anything other than bribes. While it is laudable to offer her the benefit of the doubt, the reality is that she did receive these gifts from developers. And developers have more impact on the design and function of our city than any other single business constituency.

While we can defend Dixon’s sincere love for her city, her ambitious agenda, her mostly-functional administration, and her political bravery, the tragic truth is that she fell victim to the inherent flaws of the very place that made her. The culture of personal gain over civic duty is pervasive and inescapable in Baltimore. And the government accurately reflects the values of its people.

Our cities plod along, hostage to the special interests and powerful “players” to whom we have consigned our urban future. We have enabled and continue to refine a new system of urban feudalism, its landscape populated by warlords each concerned with their own particular brand of self-interest. There is precious little difference between a corner drug dealer and the Mayor of Baltimore when everybody’s on the take.

A Path to Recovery

It is easy to complain about American public life and politics, and real solutions are hard to find. James Fallows argues in this Atlantic Monthly article that while the American system of government has been horribly hamstrung by special interests, the only hope we have is continued engagement. He argues that we cannot divorce public life and the private sector, as both fail when that happens.

I believe there may be yet another pathway forward, inspired by the great American thinker and architect Buckminster Fuller’s quote: “You never change things by changing the existing reality. Instead, build a new model that makes the existing reality obsolete.” If there is a way forward it is in this direction.

Public Life Without Politics

We have become accustomed to the idea that participation in public life comes only in the form of elected office or through lumbering nonprofit organizations. But there is an emergent form of public engagement centered around alignment behind ideas. The Internet has enabled likeminded people to converge both online and in the real world to achieve amazing goals, all without the burdens of machine politics and the slow-moving governance of nonprofits.

American cities offer an exceptionally strong opportunity for our country to return to competitiveness on the world stage. Compact, efficient, and diverse, our cities are platforms upon which we can design an economic life predicated on two key core values: respect for place, and respect for people and their time.

If we truly love our place and our people, competitive advantage will flow naturally from there. Embracing our cities is a pro-business agenda. It’s a future where everyone wins.

An Apolitical Future

Until recently, the flow of information to citizens has been imperfect and incomplete, and political parties have acted as proxies to enable people with similar values to coalesce.

But as information flow becomes more perfect and attitudinal alignment can occur in higher-resolution ways, political parties may no longer be effective channels for achieving important public goals.

To the extent that people can rally around goals and achieve real results using apolitical modern organizing efforts, we may find that the future of public life lies in individual action rather than in elected office or in nonprofit organizations.

Our country’s future demands that we find the answer.

November 7th, 2009 — art, baltimore, business, design, geography, philosophy, trends

In 1983 at age 12, I became drawn to the design and tech culture of San Francisco. By that time I was already deeply involved in computers and the other tech of the day, and had been reading every issue of BYTE Magazine cover-to-cover when it arrived in our mailbox after school.

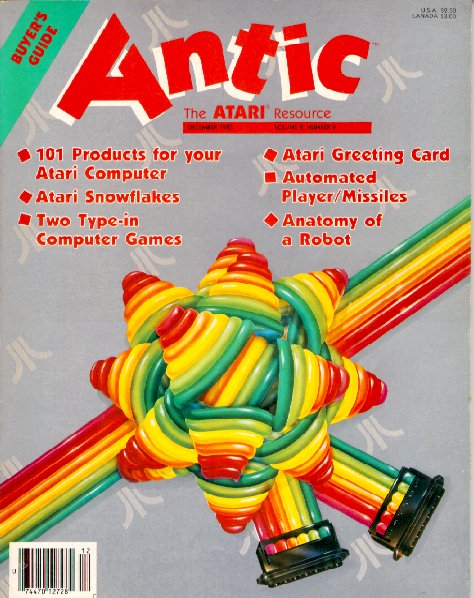

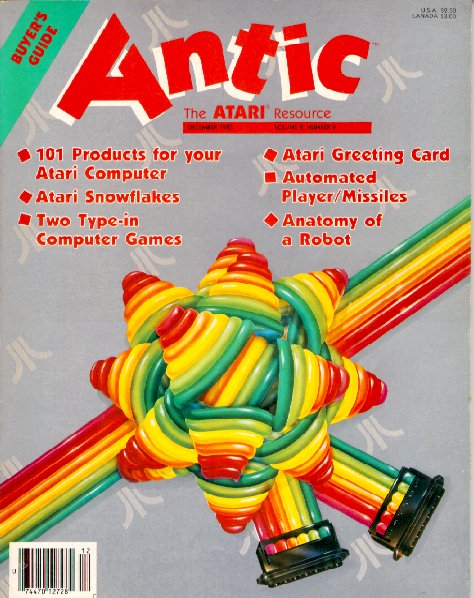

BYTE was produced in New Hampshire and had a scholarly tone; still, the emerging world of computing was breathlessly covered, and offered a sense of endless possibility. But it was Antic magazine (a specialty computing magazine for Atari computers), specifically the December 1983 “Buyer’s Guide” issue that really caught my eye.

The design was colorful and imaginative, with beautiful typography, and the magazine was full of amazing ideas and products which I was sure would launch me on my way to unlimited exploration. I devoured the magazine cover to cover, but I never realized just how much I was soaking up its design ethos. Colorful, playful, and bold, this was not the wry, academic BYTE. It was combining the substance of tech with the emerging design scene in San Francisco, and it resonated with me profoundly.

In 1985, I got a job at a local computer store doing what I loved: selling computers and software and, yes, copies of Antic magazine. In 1986, I started my own computer and software sales company, Toad Computers. In 1989, months after graduating from high school, I had the chance to visit Antic Magazine — this time as an advertiser.

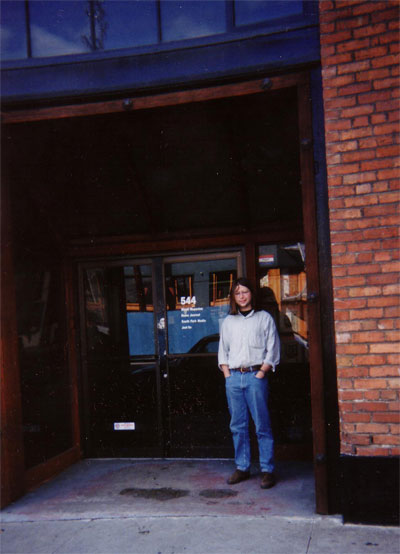

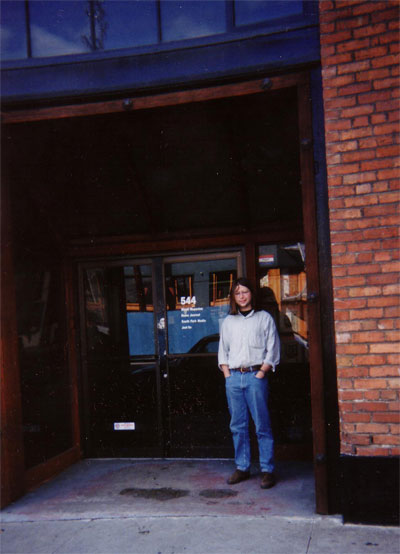

This was my first trip to San Francisco and I visited Antic at their loft office, located at 544 Second Street, right in the heart of the city’s SOMA district. But this was SOMA before it was the SOMA we know now as the home of so many startup tech companies. Beat up and edgy, the open-air second floor office had high-beamed ceilings and gave a sense of history and limitless potential. I was smitten with the city and with valley tech culture – I also visited Atari’s headquarters in Sunnyvale that trip – and absorbed all that I saw.

Later in 1993, I was twenty-one and searching for new things to explore. Toad Computers was doing well but I knew that it would have to change and grow to survive. Atari was having tough times. Antic magazine had folded. To advertise effectively we were sending out massive catalog mailings, featuring 56 page catalogs that I personally designed – very much in the visual style of Antic magazine.

Someone had told me about a new magazine called Wired. I picked up a copy and was immediately struck with its sense of visual design and its aura of infinite possibility through the combination of design and tech. Again, I ingested every word, photo, and illustration in each issue. In early 1994, I noticed an ad that indicated that Wired – this tiny publishing startup – was looking for a circulation manager. I was entranced at the possibility. With my background in direct marketing and managing big catalog mailing lists, I thought this might be an opportunity for me.

In February 1994, I booked a trip to San Francisco to talk to my kindred spirits at Wired about the possibility of working there. I also became entranced with the Internet and its possibilities at this time, and for several days before my trip to San Francisco, I worked feverishly to write an article for Wired about how the Internet – when it became fully developed and evolved – could become a kind of real-time Jungian web of knowledge that acted like a global brain cheap kamagra oral jelly uk. I theorized that the Internet could become a kind of collective consciousness that enabled humanity’s genius to be available to everyone all the time. I predicted online banking, shopping, and video chat and made illustrations to show how these things would work.

Me, with long hair, at Wired HQ in February 1994

Of course, the simple things were not hard to predict at that time, though they were still a few years off. But my central thesis about Jungian synchronicity was just too wacko to print in 1994. And to be fair, I had cobbled the article together in just a couple of days, had worked in ample quotes from Marshall McLuhan and Carl Jung, and had interviewed no one. My thesis may have been strong, but the piece would have benefited from some interviews and editing. But hey, I was inspired and twenty-two.

When I went to Wired’s offices, I was stunned to learn that they were located in the same office that Antic had occupied! The same open air loft office at 544 Second Street. I met with some folks from Wired’s barebones staff. I commented on my perceived sense of Jungian synchronicity — about Antic and Wired sharing the same office space. We talked about job possibilities. I submitted my article.

I didn’t get a job, and they didn’t print my article. To be fair, I wasn’t really ready to move to San Francisco, and I am sure they sensed that. I also wasn’t sure what I wanted. I just knew that I was drawn to this hopeful admixture of design and tech that seemed to emanate, radio-like, from 544 Second St.

In March 2007, two weeks after I had built Twittervision and a week after SXSW launched Twitter onto the early adopter stage, I thought it would be fun to stop by Twitter HQ in San Francisco. I met Biz and Jack and Ev, and was once again amazed to see that something I had been drawn to had come from SOMA; just a few blocks from 544 Second St. And ironically, it is now Twitter and the “Real Time Web” that is beginning to enable the kind of global consciousness that I had predicted in 1994.

This past Thursday at TEDxMidAtlantic (of which I was the lead organizer and curator) in Baltimore, I was struck by the beautiful design of our stage set. (Thanks to Paul Wolman at Feats, Inc. for bringing it together for us!) A simple combination of bookshelves, cut lettering, books, a few objects and blue wash backlighting had combined to produce a gorgeous backdrop for the extraordinary ideas that our speakers would soon be sharing. And I felt at home. I could not go to 544 Second Street and SOMA. Instead, it was my mission to bring it here.