February 5th, 2009 — baltimore, business, design, economics, philosophy, social media, software

The First Church of American Business teaches that virtue accrues from execution, and that the ability to manage big, complex to-do lists either personally or via delegation is the key to getting ahead in business.

From there it also holds that competition is all about having and managing longer and more complex to-do lists, and beating out the other guy who’s presumably doing the same thing. Books with titles like “Execution,” “Getting Things Done,” and the “7 Habits of Highly Effective People” depict the business world as a crazy-making self-perpetuating scheme of testosterone-fueled competition, which ultimately aims to canonize its Saints the way the sports world does its highest trophy winners.

Business book writers have it particularly easy; they go back and look for the “winners” of this apparent competition (Jack Welch, Bill Gates, Eric Schmidt) and assign them all manner of superhuman qualities. Occasionally they come across somebody who somehow managed to get on top without shaming (and presumably out-executing) all of his or her peers, and they shrug in disbelief and assume that they must have “the vision thing” and canonize the schmuck anyway; the last thing the high priests of productivity would want to admit was that they didn’t see someone coming.

My deepest wish is to go back to 1960 or 1985 (maybe both) and gouge out the eyes of these practitioners with their own tassel loafers. We’ve seen how this all worked out; this approach to business has led us to the only place it could: a testosterone-fueled sham of an economy.

Certainly execution is important. But in the rush to assign virtue to execution itself, we’ve lost sight of what it is we’re executing – that “vision thing.”

Design is the most important force for good in the world today. Overstated? I don’t think so. Design indicates intent. I believe humanity has good intentions for the world; therefore I believe that design is the way in which we will manifest those good intentions.

Many people are confused about what design is. They confuse it with industrial design (iPod, Beetle, Aeron Chairs) or graphic design (packaging, advertising, marketing, websites), or simply assume it’s one of those “art things” that they don’t have to worry about because they didn’t study it in business school.

But in fact, people design things every day. We are all designers of our lives. In the simplest choices, we are signaling our intentions about how we want to interact with the world and sending subtle cues about the kinds of interactions we desire.

Getting good at design is a little bit like becoming a Jedi master – it comes from a place inside where less is more and where silence is more powerful than sound. It’s about looking for the reasons why something will work rather than the ways it might fail. It’s about finding the line, the melody, the art, the poetry in mundane transactional details and teasing it out to make it serve you. It’s tough to explain, but over the next few days, I’ll be reviewing some recent, unconventional examples of design in my own experience.

Design is all about executing a small number of the right tasks.

January 16th, 2009 — art, design, economics, geography, philosophy

A few weeks ago, my wife picked up a book called The Written Suburb at a Greenwich Village used bookshop about Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, and how it was an invented, postmodern place, designed to become a mythological homeland of the American realist movement.

As the area was home to painters like Howard Pyle, N.C. Wyeth, and Andrew Wyeth, its history was certainly intertwined with that of American art. The Brandywine River Museum has done a fine job selling itself as the First Church of Delaware Valley Realism and enhancing the myth of Brandywine River as a seat of not just Realism but also of the Real.

As a teenager, I had visited the Brandywine River Museum, and when pressed to write a paper for an art class, I chose to write about the work of Maxfield Parrish, the prolific American illustrator whose work is featured there. I was enchanted by his technical method, which employed multilayer transparencies and unusual materials, but my teacher disputed that his stuff was really “art” and undoubtedly had wished I’d chosen to write about Picasso or Millet — somebody “real.”

With the news of the death of Andrew Wyeth, the whole question of whether the Brandywine River school really produced “art” is back in the news again. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York refused to show his “Helga” paintings on the grounds that they were not, or at least weren’t very good.

The Museum of Modern Art keeps Andrew Wyeth’s most famous work Christina’s World (1949) in a back corner, and it’s always fun to watch people discover its presence. They stumble upon it, and are surprised at how it moves them. As an icon, they are completely ready for it to be trite and clichéd, but in person it still seems to catch people up.

Art purists would say that the only valid art is work that’s done for art’s sake alone: without guile, without intention to build an audience, without regard to populism. Arguably, only art that fits this definition can advance what’s been done before it in the same vein: populism and intellectual progress usually don’t mix.

However, another definition of art is any work that conveys emotion, and on this score, the Wyeths and the Brandywine River School perform well enough to merit attention. That 200 million people can name Wyeth as one of their favorite artists shows his communication has been effective, however invented or populist it may be.

The intersection between art, populism, and commerce is an interesting place to poke around. Here are the seams of our culture, where values, money, and progress bang up against each other.

The Brandywine River Museum touts the artistic authenticity of an invented place, and the Wyeths, Pyle, and Parrish are all promoted as invented artists, designed to insure the flow of tourist dollars into Chadds Ford and Kennett Square — beautiful places, to be sure, and if you squint you can convince yourself the place conveys the feelings the art is trying to make you feel — especially at this time of year, when the browns, greys, white and cold look and feel just like a Wyeth landscape.

But in the end, that’s a leap of faith on the part of the viewer. Sometimes art requires the viewer to become complicit in its own invention.

January 2nd, 2009 — business, design, economics, trends

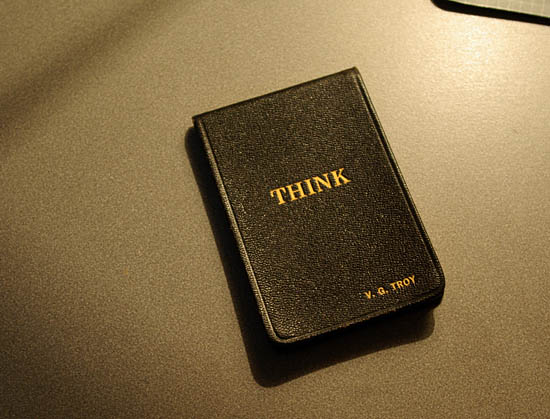

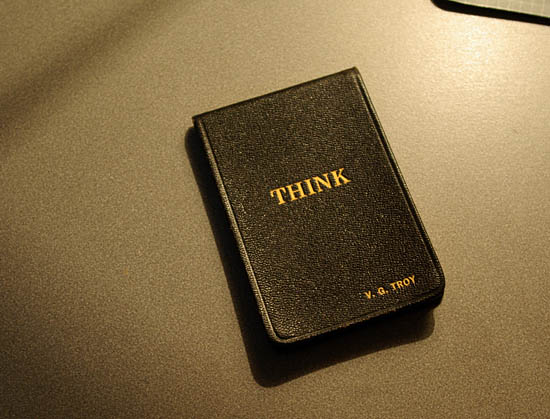

Yesterday at my parents’ house I stumbled across a small black 3″ x 4″ leather-covered notepad with the word “THINK” on it in gold, and my grandfather’s initials (V. G. TROY) embossed in gold in the lower right corner.

This was an original IBM Think Pad.

Thomas Watson, founder of IBM, famously instructed his employees to “THINK” and had emblazoned the word all over the company’s offices; each employee carried a “THINK” notepad. And it seems they gave out various similarly-themed promotional material: my grandfather was a prospective customer to IBM, as he managed the automation of the New York State Insurance Fund in the early 1960’s. My wife recalls that her great-grandfather, an accountant, had a large “THINK” sign over his desk, presumably encouraging his supplicants to refine their queries.

I got to considering what it says about a company (arguably a society’s largest and most successful company) that is so fanatical about a single word like THINK. And what does it say about a company (and a society) that abandons that slogan?

THINK, in all caps and repeated like a mantra, says a lot. It implies that as individuals we are capable of logical contemplation that will result in conclusions that are universally true; that there is in fact one truth that all of us can visualize if we simply utilize our intellect and the tools of logic. What a view of the world (and of business) this is: there is only truth, there is only competitive advantage, there is only logic. If you want to succeed, all you have to do is find the truth.

Somewhere in the last 40 years, American business became unglued from truth.

Success in business became a kind of alternate-reality game, with a billion realities competing against one another, and perception trumping reality. No wonder a word like THINK seems obsolete and quaint now: it ignores the reality of Wall Street and all the complexity that comes when you’re painting a different picture for customers, employees, and shareholders.

If we were to choose a word that sums up the current business ethos, it might be something like “POSTURE” or “PROFIT”. But it’s surely not THINK; thinking has been out of fashion for some time, and it may just be that as we dismantle this fake, Bernie Madoff economy, we discover that if we want to achieve real economic success again we could do worse than to adopt Mr. Watson’s old mantra.

THINK.

December 31st, 2008 — business, design, economics, trends

Nearly every weekday between 4:00 and 7:00pm, eastbound US Route 50 in Annapolis, Maryland comes to a standstill. It typically happens near the westernmost edge of the city, and for a distance of roughly 7 miles, traffic inches along at a speeds often less than 10 miles per hour.

Yesterday it took me 30 minutes to cover these 7 miles (5:30 to 6:00pm).

It would be one thing if it was just me that was inconvenienced, or if this was a result of an accident or some unusual circumstance, but not so: this happens every day and there are tens of thousands of people affected by it. There is nothing unusual about it. We can only infer that this is how the road was designed to operate.

It would also be one thing if it was just this stretch of Route 50 that was affected by this kind of thing, but we all know it’s not. The Washington Beltway, to take one well known local example, is also apparently designed to fail spectacularly every morning and afternoon (and sometimes in between).

What does it say about a society that has its citizens sit in bumper-to-bumper traffic, day in and day out, spewing CO2 and other pollutants and wasting their time?

To me, it’s a sign of contempt. Anyone that would knowingly have people spend their time (and fuel) this way, day after day, must be filled with utter disdain for those so effected. Who’s to blame for these designs?

Surely there are some highway planners and road builders that could take the blame, but I have to think that any changes to the roads themselves can only yield marginal improvements — however needed those improvements may be.

The real issue boils down to us — the citizenry — and where we invest our financial and political capital. We are to blame.

We are the ones who have repeatedly failed to fund public transportation initiatives acquisto viagra. We are the ones who have lacked the foresight to discourage long distance car commutes. Annapolis residents famously rejected the extension of the Washington DC metro along the US 50 median because it would “bring crime” from the big city. Now Annapolis is its own capital of crime, and DC is further away than ever by car. And the median strip that once could have accommodated the metro has been sacrificed to ineffective additional lanes. Opportunity lost.

So, there you have it: we’ve locked ourselves into an economic model that provides long term competitive disadvantage. While other countries make good use of public transport and respect people’s time by moving them around efficiently, lowering pollution and making people more productive in the process, we’re stuck in the 1970’s, with people killing 2-4 hours per day in their cars spewing gases. Nice.

| Severn River Bridge Backup, US 50 |

| Miles |

7 |

| Lanes |

5 |

| Hours in Backup |

0.5 |

| Average Car Length (ft) |

20 |

| Number of Cars/Lane |

1848 |

| Number of Cars |

9240 |

| Number of Cars/Hour |

18480 |

| Number of Hours/Day |

3 |

| Number of Cars/Day |

55440 |

| Idle Fuel Consumption/Hr |

0.5 |

| Gallons Fuel/Car |

0.25 |

| Fuel Cost |

1.6 |

| Fuel Cost/Car |

0.4 |

| Total Cost/Day |

$22,176.00 |

| CO2 Generation/Gallon (lb) |

22 |

| Total Gallons Gas |

13860 |

| Total CO2 Output |

304,920.00 |

| Tons CO2 Output |

152.46 |

| Man Hours |

27720 |

| Average Hourly Rate |

$15.00 |

| Lost Value |

$207,900.00 |

So every day, by design, this SINGLE stretch of Route 50 causes at least $207,900.00 in lost productivity for people, costs $22,176.00 in fuel (at $1.60/gallon — try it at $3.99), and generates 152.46 TONS of CO2 output. And that’s when it’s working AS DESIGNED! This is what it’s SUPPOSED to do??!?

Go ahead and add in every other backup in Maryland — the DC Beltway, the Baltimore Beltway, I-95, I-83 for starters — and you’ll have an amazing amount of lost time, energy, and productivity! It’s staggering what a drag this is on our economy. And the first instinct we citizenry has is to expand the current roads and build new ones. And this won’t help!

The only things that will really help are to 1) work closer to where you live, 2) use public transportation or bikes to get there, 3) improve the design of the roads we have.

The inability (er, unwillingness) to make this happen in suburban America is why places that have better public transportation (and the vibrant work/residential communities that invariably build up around it) will outpace us in the long term.

We simply can’t compete in the world economy if we’re locked up in our cars.